- Wild animals

- >>

- Insects

The Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) is an insect belonging to the order Coleoptera and the family of leaf beetles, belongs to the genus Leptinotarsa and is its only representative.

As it turned out, the homeland of this insect is the northeast of Mexico, from where it gradually penetrated into neighboring territories, including the United States, where it quickly adapted to climatic conditions. Over the course of a century and a half, the Colorado potato beetle has spread literally throughout the world and has become the scourge of all potato growers.

Origin of the species and description

Photo: Colorado potato beetle

The Colorado potato beetle was first discovered and described in detail by American entomologist Thomas Sayem. This happened back in 1824. The scientist collected several specimens of a beetle hitherto unknown to science in the southwestern United States.

The name “Colorado beetle” appeared later - in 1859, when an invasion of these insects destroyed entire potato fields in Colorado (USA). After a couple of decades, there were so many beetles in this state that most local farmers were forced to give up growing potatoes, despite the fact that their price had increased significantly.

Video: Colorado potato beetle

Gradually, year after year, in the holds of sea ships that were loaded with potato tubers, the beetle crossed the Atlantic Ocean and ended up in Europe. In 1876 it was discovered in Leipzig, and another 30 years later, the Colorado potato beetle could be found throughout Western Europe except Great Britain.

Until 1918, the breeding grounds of the Colorado potato beetle could be successfully destroyed, until it managed to settle in France (Bordeaux region). Apparently the climate of Bordeaux was ideal for the pest, as it began to rapidly multiply there and literally spread throughout Western Europe and beyond.

Interesting fact: Due to the peculiarities of its structure, the Colorado potato beetle cannot drown in water, so even large bodies of water are not a serious obstacle for it in its search for food.

The beetle allegedly entered the territory of the USSR in 1940, and after another 15 years it was already found everywhere in the western part of the Ukrainian SSR (Ukraine) and the BSSR (Belarus). In 1975, the Colorado potato beetle reached the Urals. The reason for this was a long, abnormal drought, due to which livestock feed (hay, straw) was brought to the Urals from Ukraine. Apparently, a pest beetle also came here along with the straw.

It turns out that in the USSR and other countries of the socialist camp, the mass spread of the beetle coincided with the beginning of the so-called “Cold War”, so accusations of an unexpected disaster were addressed to the American intelligence service CIA. Polish and German newspapers even at that time wrote that the beetle was deliberately thrown into the territory of the GDR and Poland by American aircraft.

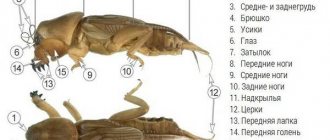

Description

The Colorado potato beetle is a representative of the leaf beetle family, belonging to the order Coleoptera. Both adults and larvae feed mainly on the foliage of cultivated nightshade plants, and less often on flower and wild nightshade plants.

The structure of the Colorado potato beetle will be as follows:

- the body is ovoid, oval in shape, its upper part is convex, the lower part is flat, its length can be from 7 to 12 mm, and its width from 4.5 to 10 mm;

- the head is inconspicuous, as it is slightly retracted and located almost vertically, has a rounded shape, wider than it is long; there is a black mark on the head, shaped like a triangle with equal sides;

- on the head there are eyes, bean-shaped, black, located on the sides;

- at the level of the anterior region of the eyes there are antennae consisting of eleven segments, the first five of which are colored brown, the rest are black;

- the elytra are rigid, tightly fitting to the body, the main color is yellow, and each has five longitudinal black stripes;

- thin and weak legs have a special structure, thanks to which the Colorado potato beetle is only able to crawl;

- the abdomen is colored light orange and is divided into seven segments, along which black spots run in rows.

Often female Colorado potato beetles look different from males. The former are usually larger and weigh slightly more. An overwintered male half can weigh on average 145 mg, and a female half can weigh 160 mg.

Appearance and features

Photo: Colorado potato beetle in nature

The Colorado potato beetle is a fairly large insect. Adults can grow up to 8 - 12 mm in length and approximately 7 mm in width. The body shape of the beetles is somewhat reminiscent of a water drop: oblong, flat at the bottom and convex at the top. An adult beetle can weigh 140-160 mg.

The surface of the beetle's body is hard and slightly shiny. In this case, the back is yellowish-black with black longitudinal stripes, and the belly is light orange. The beetle's black oblong eyes are located on the sides of its round and wide head. On the head of the beetle there is a black spot similar to a triangle, as well as movable, articulated antennae, consisting of 11 parts.

The hard and fairly durable elytra of the potato beetle fit tightly to the body and usually have a yellowish-orange, less often yellow, color, with longitudinal stripes. The wings of the Colorado potato beetle are membranous, well developed, and very strong, which allows the beetle to travel long distances in search of sources of food. Female beetles are usually slightly smaller than males and do not differ from them in any other way in appearance.

Interesting fact: Colorado potato beetles can fly quite quickly - at a speed of about 8 km per hour, and can also rise to great heights.

What does a beetle look like?

Colorado potato beetle

The Colorado potato beetle is a frequent visitor to fields and vegetable gardens, so many have seen it more than once.

- Insects have orange colored modified wings that fit tightly to the body. Each elytra has five black stripes. Colorado potato beetles are easy to recognize by their coloring.

- The length of the body can reach 15 mm, width – 7 mm.

- If you look closely at the photo of the Colorado potato beetle, you will see that it has a convex part on top and a flat part on the bottom.

- The rounded, retracted head of the insect is very small, much smaller than the body. There are black eyes on its sides. The organs of touch are the antennae, which consist of 11 segments.

- The abdomen is decorated with black spots arranged in rows.

- The beetle's legs, numbering three pairs, are poorly developed. They have peculiar hooks, thanks to which the pest easily crawls along the leaves.

Interesting!

The Colorado potato beetle flies thanks to its membranous, well-developed wings. It easily makes long-distance flights, exploring new habitats. Beetles fly only in warm weather, before they have to overwinter.

Where does the Colorado potato beetle live?

Photo: Colorado potato beetle in Russia

Entomologists believe that the average lifespan of the Colorado potato beetle is approximately one year. At the same time, some more hardy individuals can easily endure winter and even more than one. How do they do it? It’s very simple - they go into diapause (hibernation), so for such specimens, even three years of age is not the limit.

In the warm season, insects live on the surface of the ground or on the plants they feed on. Colorado beetles wait out autumn and winter, burrowing up to half a meter into the soil, and calmly tolerate freezing there down to minus 10 degrees. When spring comes and the soil warms up well - above plus 13 degrees, the beetles crawl out of the ground and immediately begin to look for food and a mate for procreation. This process is not too massive and usually lasts for 2-2.5 months, which greatly complicates the fight against the pest.

Despite the fact that the habitat of the Colorado potato beetle has increased almost several thousand times over the course of a century and a half, there are several countries in the world where this pest has never been seen and has no idea how dangerous it is. There are no Colorados in Sweden and Denmark, Ireland and Norway, Morocco, Tunisia, Israel, Algeria, and Japan.

Now you know where the Colorado potato beetle came from. Let's see what he eats.

Damage caused by the beetle

The larvae of this pest are particularly voracious. Under favorable conditions (warm weather) they develop much faster. Under such conditions, the number of larvae in the garden is in the thousands. It only takes a couple of days for them to cause serious damage to the potato crop: they will eat all the leaves and only the stems will remain. In such cases, you cannot count on a good potato harvest. Therefore, you should not hesitate to destroy the beetle.

It also harms other crops of the nightshade family. These include:

- Potato.

- Tomatoes.

- Salad pepper.

- Eggplant.

Interesting to know! The Colorado potato beetle feeds not only on green shoots of potatoes, but also on tubers, especially in the spring, when green shoots have not yet emerged from the ground. During this period, the beetle can be easily controlled using traps. Shredded potatoes are used as bait. The beetle has become hungry over the winter, so it will immediately attack the bait.

A simple way to get rid of the Colorado potato beetle forever

What does the Colorado potato beetle eat?

Photo: Colorado potato beetle on a leaf

The main food of Colorado beetles, as well as their larvae, are young shoots and leaves of plants of the nightshade family. Beetles will find food wherever potatoes, tomatoes, tobacco, eggplants, petunias, sweet peppers, and physalis grow. They do not disdain wild plants of this family.

At the same time, beetles like to eat potatoes and eggplants most of all. Insects can eat these plants almost completely: leaves, stems, tubers, fruits. In search of food, they are able to fly very far, even tens of kilometers. Despite the fact that insects are very voracious, they can easily endure forced hunger for up to 1.5-2 months, simply falling into short-term hibernation.

Due to the fact that the Colorado potato beetle feeds on the green mass of plants of the nightshade family, a toxic substance, solanine, constantly accumulates in its body. Because of this, the beetle has very few natural enemies, since the beetle is simply inedible and even poisonous.

Interesting fact: Curiously, the greatest harm to plants is caused not by adult Colorado potato beetles, but by their larvae (stages 3 and 4), since they are the most voracious and are capable of destroying entire fields in a few days under favorable weather conditions.

How to determine that it is a Colorado potato beetle?

The Colorado potato beetle is quite difficult to confuse with any other potato pest. It is recognized by its characteristic color:

- Larvae that have just emerged are first gray and then acquire a bright reddish-orange hue.

- The larvae grow in a couple of weeks, already at an ambient temperature of +12 degrees. During this period, they are able to destroy all the leaves on the potatoes and leave only the stems.

- The larvae have a body that is unpleasant to the touch, although they are somewhat disgusting in appearance. It is fleshy and convex on the outside, and also flat on the bottom. On the sides you can see sparse bristles. If the larva is accidentally crushed, a bright, yellow-colored and unpleasant-looking liquid is released.

- Grown-up individuals reach a size of 1.5 cm, and they actively eat the leaves of nightshade crops.

- Adult beetles are distinguished by dense elytra, on which black stripes are located along. The beetle is distinguished by its yellow-red or reddish-orange color. The beetle's legs are black.

- Thanks to the tenacious claws placed on its paws, the pest can easily move across plants and other surfaces.

- An adult beetle grows up to 1.2 cm in length and has an oval body, up to 7 mm wide. Although the beetle itself is not large in size, the harm it causes is simply enormous.

Features of character and lifestyle

Photo: Colorado potato beetle

The Colorado potato beetle is very prolific, voracious and can quickly adapt to various environmental factors, be it heat or cold. The pest usually survives unfavorable conditions by hibernating for a short time, and can do this at any time of the year.

The young Colorado potato beetle (not the larva) is bright orange in color and has a very soft outer covering. Within 3-4 hours after birth from the pupa, the beetles take on a familiar appearance. The insect immediately begins to feed intensively, eating leaves and shoots, and after 3-4 weeks reaches sexual maturity. Colorado potato beetles that were born in August or later usually hibernate without offspring, but most of them will make up for this loss the following summer.

One of the features unique to this type of beetle is the ability to go into long-term hibernation (diapause), which can last 3 years or even longer. Although the pest flies beautifully, which is facilitated by strong, well-developed wings, in moments of danger for some reason it does not do this, but pretends to be dead, tucking its paws to its abdomen and falling to the ground. Therefore, the enemy has no choice but to simply leave. Meanwhile, the beetle “comes to life” and continues to go about its business.

Development with the transformation of the Colorado potato beetle

Colorado beetle larva

With the onset of spring, Colorado beetles crawl to the surface. After 5-6 days, their reproduction begins. This process continues until autumn. After mating, females find secluded places and hide Colorado potato beetle eggs in them. Their number varies from 20 to 70 pieces. The male and female mate most intensively in sunny, clear weather. Most often this happens in the afternoon or midday hours.

Eggs can be seen on the leaves (on the reverse side), as well as on the shoots. Larvae appear after 7-21 days. They go through the process of pupation and with the onset of summer time they turn into adults. If you look at a photo of a Colorado potato beetle larva, you can clearly see the curved back of the red-orange color, which changes as it grows. It turns orange with a yellowish tint.

On a note!

The peculiarity of the larvae is the presence of two rows of black dots on the sides. They are very voracious, but initially feed only on the pulp of plants, later they completely eat the shoots. Therefore, the fight against Colorado potato beetle larvae in vegetable gardens and fields is inevitable, as this will help preserve the harvest.

There are different methods for their destruction: mechanical, biological, agrotechnical with the use of chemicals. As a result of the actions taken by humans, the beetles must die.

Social structure and reproduction

Photo: Colorado beetles

As such, Colorado beetles, unlike other types of insects (ants, bees, termites), do not have a social structure, since they are solitary insects, that is, each individual lives and survives on its own, and not in groups. When it becomes warm enough in the spring, beetles that have successfully overwintered crawl out of the ground and, having barely gained strength, the males begin to look for females and immediately begin mating. After the so-called “mating games,” fertilized females lay eggs on the underside of the leaves of the plants on which they feed.

One adult female, depending on the weather and climate of the area, is capable of laying approximately 500-1000 eggs during the summer season. Colorado eggs are usually orange, 1.8 mm in size, oblong-oval, located in groups of 20-50 pieces. On days 17-18, the eggs hatch into larvae, which are known for their gluttony.

Stages of development of Colorado potato beetle larvae:

- in the first stage of development, the larva of the Colorado potato beetle is dark gray in color with a body up to 2.5 mm long and small thin hairs on it. It feeds exclusively on tender young leaves, eating away their pulp from below;

- at the second stage, the larvae are already red in color and can reach sizes of 4-4.5 mm. They can eat the entire leaf, leaving only one central vein;

- in the third stage, the larvae change color to red-yellow and increase in length to 7-9 mm. There are no longer any hairs on the surface of the body of individuals of the third stage;

- at the fourth stage of development, the beetle larva changes color again - now to yellowish-orange and grows to 16 mm. Starting from the third stage, the larvae are able to crawl from plant to plant, eating not only the pulp of the leaves, but also young shoots, which causes great harm to the plants, slowing down their development and depriving farmers of the expected harvest.

All four stages of development of the Colorado potato beetle larva last approximately 3 weeks, after which it turns into a pupa. “Adult” larvae crawl into the soil to a depth of 10 cm, where they pupate. The pupa is usually pink or orange-yellow. The duration of the pupal phase depends on the weather. If it’s warm outside, then after 15-20 days, it turns into an adult insect that crawls to the surface. If it’s cool, this process can slow down 2-3 times.

How to get rid of the Colorado potato beetle

There are two ways to combat this voracious pest: the use of chemicals and mechanical collection. The latter method, although labor-intensive and suitable only for small potato planting areas, is effective. In addition, no toxic substances are used in the garden, which is important, since one-time treatment with chemicals is unlikely to be sufficient. Using chemicals is a quick way to get rid of beetles in the garden, although there is a risk of poisoning. This is the only way to destroy the beetle in large areas of potato plantings.

In any case, an integrated approach is needed, including the use of agrotechnical measures, although with the Colorado potato beetle everything is not so simple: it burrows into the ground to great depths and waits out the winter. Therefore, if you dig up your garden in the fall, you will not be able to get rid of the beetle.

Chemical control agents

For those who want to quickly get rid of such a pest, there is a large selection on the market of insecticidal and acaricidal chemicals. It’s better to take a couple of drugs to determine which one is more effective, but you shouldn’t get too carried away with chemistry and conduct experiments in your garden. The fact is that the beetle has already managed to adapt to some of them, so the fight may be ineffective, and the person may suffer.

Need to know! The greatest effect can be obtained if systemic drugs are used. By eating a plant, a toxic substance enters the pest’s gastrointestinal tract, after which the insect dies.

In the fight against the Colorado potato beetle, the following is used:

- Prestige.

- Decis.

- Karate.

- Fitoverm.

- Aktar.

- Inta-Vir.

- Bushido.

- Colorado.

- Regent.

- Sonnet.

Mode of application:

- Processing of potato, tomato, pepper and eggplant plantings should be carried out early in the morning or late in the evening, when the sun's exposure is minimal. In hot weather, it is prohibited to treat the area, as you can be poisoned by the fumes of the drug.

- The use of toxic drugs is limited to a certain period - 2 months before the start of harvest. Failure to do so may result in poisoning of family members.

- It is better to use a backpack-type sprayer. The sprayer is selected depending on the area of potato planting.

- Before using a chemical, a solution is prepared based on it according to a certain proportion specified in the instructions. It is not recommended to violate the proportions in either direction.

- Treatment of the area is carried out only in protective clothing. As a rule, glasses, rubber gloves, a respirator or gauze bandage, long-sleeved clothing (preferably old and unnecessary), and shoes are used.

- You should not eat while spraying, and after work you should thoroughly wash your hands, rinse your mouth and wash your face. Clothes need to be washed to be reused, or better yet, thrown away.

SUPER REMEDY THE BEETLE DIES ON THE FLY AND THE POTATOES ARE SAVED

Folk remedies

As a rule, infusions and decoctions are used that negatively affect the life activity of this voracious pest: they either destroy the beetle or give the green potatoes an unpleasant taste for the beetle. As a result, the beetle refuses to eat potatoes. At the same time, you need to use folk remedies on a regular basis.

Tested means include:

- Infusion based on tomato tops . To prepare the active composition, you will need tomato greens (leaves and shoots) and a bucket of boiling water. This boiling water is poured over the green tomatoes and left for about 5 hours. After this, the product is filtered, after which the plantings of garden crops, which the beetle prefers to feast on, are sprayed with it. For greater effectiveness, you can add 50 g of soap (can be liquid) to the solution.

- A decoction based on soap and hot pepper . Take 10 liters of water, put it on the fire and bring it to a boil, after which 100 g of dried hot pepper is added to the water and boiled for 2 hours. Once the solution has cooled, add 40 grams of soap shavings to it and mix well. After this, you can begin to process the plantings of potatoes and other plants.

- Decoction based on walnuts . To prepare the solution, you need to take young leaves and fruits, then pour 10 liters of boiling water over them. The product is infused for a week. After this, the product is filtered and the garden is sprayed with it.

- Decoction of celandine . Take half a bucket of raw materials and fill it with hot water, slightly boil it and strain it. The spraying agent is prepared in the following proportion: half a liter of decoction is taken per 10 liters of water.

- Infusion of onion peel . Take 300 g of onion peels and boiling water, but enough to cover the peels. The product is infused for 24 hours, filtered and used to combat this voracious pest.

Use of dry products to combat the Colorado potato beetle:

- The use of birch or pine sawdust, which is located between the rows, perfectly repels the pest.

- The use of corn flour is not to the liking of the Colorado potato beetle. When a beetle eats grains of this product, they swell in its stomach and lead to death. It is better to cultivate the garden early in the morning, when there is dew on the plants.

- If you sprinkle the soil and potatoes with ash, this will also protect the crop from the pest. It is better to take the ash after burning birch firewood.

It is possible to partially destroy the pest, especially its eggs, if you carry out high hilling of potato plantings. With high hilling, the lower leaves end up in the ground. It is on the lower leaves that Colorado beetles like to lay eggs.

An environmentally friendly product for combating the Colorado potato beetle. // Oleg Karp

DIY traps

Traps are fairly simple but effective devices for dealing with pest infestations. To make them, it is better to take plastic bottles. Just finding them is not a problem. One trap is enough for 5 square meters of garden. In short, the more traps, the more noticeable their effect.

Trap manufacturing technology:

- Take a plastic bottle and cut it off at the point of expansion.

- You need to put bait in the trap in the form of sliced potatoes.

- The container is placed in the ground, at soil level. When the trap is filled with beetles, they need to be poured out and destroyed, after which a new bait is placed in the trap.

The fight against the Colorado potato beetle is carried out annually. Unfortunately, a person cannot cope with this pest and here, oddly enough, the person himself is to blame. Unfortunately, each owner fights the beetle in his own way, and some refuse it altogether or collect it manually. Of course, no one wants toxic substances to seep into the ground every year. But it is generally unrealistic to deal with the beetle mechanically. Of course, the beetle will not eat the potatoes, but as a result, many adults will appear, which will appear in the garden again next year.

The simplest trap for the Colorado potato beetle. Saving the future harvest

Natural enemies of Colorado potato beetles

Photo: Colorado potato beetle

The main enemies of the Colorado potato beetle are the Perillus bioculatus and Podisus maculiventris bugs. Adult bedbugs, as well as their larvae, eat the eggs of Colorado potato beetles. Also, a significant contribution to the fight against the pest is made by dorifophagous flies, which have become accustomed to laying their larvae in the body of the Colorado potato.

Unfortunately, these flies prefer a very warm and mild climate, so they do not live in the harsh conditions of Europe and Asia. Also, familiar local insects feed on the eggs and young larvae of the Colorado potato beetle: ground beetles, ladybugs, lacewing beetles.

It is worth noting that many scientists believe that the future in the fight against pests of cultivated plants, including Colorado potato beetles, does not lie with chemicals, but with their natural enemies, since this method is natural and does not cause severe harm to the environment.

Some farms specializing in growing environmentally friendly products use turkeys and guinea fowl to combat the Colorado potato beetle. These poultry love to eat both adults and their larvae, since this is a feature of the species, and they are accustomed to such food almost from the first days of life.

Natural enemies

Colorado potato beetles eat potato leaves containing solanine. This substance accumulates in their tissues, so they are not suitable for food for most birds or animals. Because of this, they have relatively few natural enemies, and those that do exist cannot control beetle numbers to a harmless level.

Of the farm birds, guinea fowl, turkeys, pheasants and partridges consume beetles without harm to themselves. For them, pests are not poisonous and are eaten with great pleasure. Only guinea fowl themselves eat insects; the rest must be trained from the age of 3-4 months: first add a little crushed beetles to the food, then whole ones, so that the birds get used to their taste.

Birds can be released directly into the garden; they do not harm plants, do not rake the soil like chickens, and eat beetles and larvae directly from the leaves. Along with beetles, guinea fowl also destroy other insects that also harm cultivated plants.

There is evidence that domestic chickens also eat Colorado beetles, but only certain individuals who have been accustomed to this since childhood. Birds can be released into the garden when the larvae begin to appear, that is, already in May-June.

But it is advisable that the potatoes be fenced with something, otherwise the chickens will easily move to neighboring beds and spoil the vegetables growing there, peck out young greens, and make pits for swimming in the dust. Using poultry in this way, you can do without any treatments with chemical or even traditional insecticides.

Fighting the beetle will be completely effortless and profitable: birds, feeding on protein-rich insects, will grow quickly and gain weight, laying hens will lay a lot of eggs, and all this on free, available food.

In addition to domestic birds, the Colorado potato beetle is also eaten by wild birds. These are starlings, sparrows, cuckoos, crows, hazel grouse, etc. But, of course, you should not count on them destroying the beetle in large numbers.

It is possible to increase the number of wild birds if you specifically lure them to the site, but this takes a long time and is often not effective, so there is no point in considering wild birds as the main way to eliminate the beetle. And according to some reports, birds, having flown into the area, not only eat pests, but also spoil the harvest of berries that are ripening by this time.

Among insects, the eggs and larvae of the Colorado potato beetle are destroyed by lacewings, ground beetles, ladybugs, hoverflies, stink bugs, predatory bugs and tachinids (they infect the last, autumn, generation of the pest, thereby restraining its reproduction). Studies are underway of American entomophages - the natural enemies of the Colorado potato beetle - and the possibility of their adaptation in Europe.

Stations and wintering conditions of the Colorado potato beetle. Mortality rates in winter

The existence of the Colorado potato beetle is closely related to the soil as a habitat.

The active life of beetles (feeding, reproduction, settlement) lasts only 3-4 summer months; The beetles spend the remaining 8-9 months of the year in the soil in a state of rest (diapause, oligopause). A small number of young beetles (5-7%) enter a prolonged diapause (superpause) and can remain in the soil without coming to the surface for up to 2-3 years.

The autumn-winter period is very important for insects and often determines the physiological state and number of individuals in the spring population. The Colorado potato beetle overwinters at the adult stage in the soil, in the potato fields where its development took place or near them. Like other insects that hibernate in the soil, this pest is protected not only from the effects of low temperatures and its sharp fluctuations, but also from the danger of drying out during wintering. During wintering, beetles are inactive, so these factors - temperature and humidity - become especially important for them.

The winter survival of beetles and their condition after emerging from the soil in the spring largely depend on the conditions in which they overwintered; The type of soil, its structure, physical and chemical properties, gas and hydrothermal regimes that develop in the beetle's wintering areas determine the course of wintering and its results.

The depth of overwintering beetles depends on the type of soil and ranges from 5-10 to 70-80 cm. In light sandy soils with good regulation of gas and water regimes, beetles go to winter in deeper layers and individual individuals were found even at a depth of 100-120 cm In heavy clay soils, beetles overwinter in more superficial soil horizons. According to Ermi, in Hungary the maximum depth at which beetles were found in clay soil reached 17, and in sandy soil - 23 cm. In Belarus, where soddy-podzolic, often swampy soils predominate, the bulk of beetles overwinter in a horizon of 6-25 cm. Observations carried out in the flat part of Transcarpathia showed that the bulk of beetles (more than 90%) wintering in clay soil are concentrated in the horizon between 0 and 20 cm, and the greater half do not burrow deeper than 10 cm. The maximum depth at which they were found here beetles did not exceed 30 cm. In sandy soil, beetles are found at a depth of up to 60 cm. Of these, more than 75% are concentrated in the horizon of 10-30 cm. In the surface layers of sandy soil, beetles are found in very small numbers.

During diapause, beetles are able to move around in the soil in search of more favorable conditions. The vertical seasonal migrations of beetles are most clearly visible: in the fall, from the surface, colder layers, the beetles descend to the warmer deeper ones, and in the second half of winter and spring they migrate in the opposite direction. As a rule, by April the bulk of overwintered beetles is concentrated in the surface layers of the soil, at a depth of up to 10 cm.

It was suggested that the depth of penetration of beetles into the soil is related to their physiological state, and beetles with the most pronounced diapause go to greater depths. However, an analysis of the physiological state of beetles taken from different horizons showed that the depth of beetles in the soil does not depend on their readiness for wintering. The exception is beetles that do not have time to complete pre-diapause preparation, which go into the soil under direct cold pressure and remain in its upper layers.

The depth of insects in the soil is associated, first of all, with their requirements for the oxygen content in the soil, temperature and humidity conditions. One of the main factors limiting the penetration of insects into deep layers of soil is the lack of oxygen. A comparison of the gas composition of the air in places where beetles overwinter in soils of different types (sand, sandy loam, clay) showed that the gas regime that develops in different soils cannot serve as an obstacle to the penetration of beetles into deeper horizons for overwintering in clay soil. The differences in the concentrations of oxygen and carbon dioxide in these soils are small, but in clay soil the concentration of carbon dioxide is slightly higher and oxygen lower than in sandy and sandy loam soils, which is especially noticeable during the wintering period of beetles - from October to May. However, even during this period the difference in carbon dioxide content does not exceed 0.1-0.3%. The oxygen content also fluctuates slightly throughout the year and, on average, never falls below 20%. In spring and autumn, after rains and during the period of snow melting, conditions close to anaerobic can be temporarily created in the soil at a depth of 20-30 cm. To ensure respiration, however, a small (up to 5%) amount of oxygen is sufficient for insects, and in a state of rest (diapause, oligopause), in conditions of low temperatures, their resistance to high concentrations of carbon dioxide and lack of oxygen increases even further.

The temperature regime that develops in soils of different types, in the layers where beetles overwinter, also differs slightly. According to measurements taken in the flat regions of Transcarpathia, the temperature in clay soil in the winter months is slightly higher than in sandy soil; In the fall, clay soil cools more slowly, and in the spring it warms up more slowly. The strongest temperature fluctuations were noted in the most superficial layers of the soil, down to a depth of 10 cm. Negative temperatures (-1° -2°) were noted only at this depth, and the total number of days with sub-zero temperatures was a little more than a month in sandy soil and - in clay soil - about two weeks. At a depth of 20 cm and deeper, the temperature rarely fell below -1.5, -2.0°.

In creating the temperature regime of the soil, the height of the snow cover is of great importance, which is especially important in the northern part of the beetle’s range. Snow cover, especially freshly fallen snow, has poor thermal conductivity. This causes slow heat exchange between air and soil and protects it from rapid and deep cooling. According to Mail, at an air temperature of -18° and below, the soil temperature in an area without snow cover, at a depth of 40-60 cm, drops to -5.5, -10°, and in an area with snow cover 35 cm high, the temperature remains at a level not below - 1°. In Transcarpathia, before the snow fell (winter 1961/62), the soil temperature at a depth of 10 cm was almost no different from the temperature of its surface; after the formation of snow cover, the height of which reached 30 cm, even at an air temperature of -19°, it did not drop below -1, -2°. The mortality rate of the beetle during wintering is associated with the loss or absence of snow cover. In severe winters, with a small thickness of snowfall (less than 10 cm), mass death of beetles was observed. With an increase in the thickness of the snow cover (30 cm and above), the beetles overwintered quite safely.

Light and heavy soils differ most greatly in moisture conditions. The absolute humidity of clay soil throughout the wintering of beetles is 2 - 2.5 times higher than the humidity of sandy soil. The highest humidity in this soil was observed in the layer of mass occurrence of beetles, at a depth of up to 20 cm. In sandy soil, throughout the winter, soil moisture on average does not exceed 9-13%. In the spring at the end of March, before the beetles begin to emerge, the humidity in all soils remains at a high level.

Mortality rates of beetles during wintering vary over a very wide range. Depending on the climatic zone and year conditions, the number of dead individuals can range from 10 to 90%. According to Ermi and Scharinger, the winter mortality of beetles overwintering in peat soil reached 92.8%. In Transcarpathia, the number of beetles that died in different years and in different soils ranged from 13 to 86.8%.

The mortality rate of beetles during wintering depends on many reasons and is determined both by the physiological state of wintering beetles and by the environmental conditions prevailing in the wintering areas. The physiological state of beetles leaving for the winter and their pre-diapause preparation are very important. Beetles that did not have time to finish feeding before the onset of cold weather and are poorly prepared for wintering, as a rule, remain in the surface layers of the soil and die during wintering. Beetles of the late first generation, which developed in the second half of summer, and beetles of the second generation are less resistant to unfavorable environmental factors during wintering. As Polish scientists Kowalska and Vengorek showed, the survival rate of beetles is closely dependent on the duration of the period of their activity before the onset of diapause: the longer the period of pre-diapause feeding, the less resistant they are to unfavorable environmental factors, the higher their mortality and vice versa.

Large differences in mortality rates were noted among females that laid eggs before entering diapause and those that did not begin breeding before wintering. The mortality rate of breeding females is almost twice as high as the mortality rate of females that did not lay eggs, and the longer the oviposition period, the higher the mortality rate of females in winter.

The mortality rate of breeding females is especially high in the fall. Among females that did not lay eggs and males, the number of dead individuals fluctuated (about 25-30%), while among breeding females it reached 56%. Analysis of the state of beetles from different physiological groups showed that females that laid eggs are significantly less prepared for wintering and go into the soil with significantly lower fat reserves (by 6-11%) and with more water in the body than males and non-breeding females .

The extent of beetle mortality in the wintering population, as well as the physiological state of overwintered beetles, is largely determined by the environmental conditions in which the overwintering took place. Numerous studies of the wintering conditions of the pest have shown that light, sandy and sandy loam soils are most favorable for it; In heavy clay soils, wintering is less successful.

In heavy clay soils, the death of beetles can reach very large proportions. According to Ermi and Sharinger, the number of dead beetles in different soils ranged from 34 to 92.5%. A study of the influence of different types of soil on the wintering of the Colorado potato beetle, carried out by Pekarchik, also showed that the mortality rates of beetles are closely related to the type of soil and are: in sharp sand - 32, clay - 44, loam - 31, chernozem - 50, brown soil - 20 and in peat bogs - 30%. In Transcarpathia, during the winter seasons of 1960/61 and 1961/62. The mortality rate of beetles in clay soil was 3–7 times higher than in sandy soil, and ranged from 13 to 24.5% in sandy soil and from 46.4 to 86.6% in clayey soil. The mortality rate of beetles overwintering in sandy loam soil was slightly higher than in sandy soil, but lower than in clay soil, and ranged from 19.5 to 27.2%.

Trouvlo explains the relatively high survival rate of beetles during wintering in light soils, which is usually observed in areas with sandy soils. In France, the main potato cultivation areas are concentrated in the northwestern part of the country, where environmental conditions are less favorable for the development of the beetle: due to the strong soil moisture in winter, in these areas there is a very high mortality rate of wintering beetles and its harmfulness is not high.

The presented data on the gas and hydrothermal regime in beetle overwintering areas suggest that the main factor determining the depth of beetles for wintering in different soils and influencing the physiological state of overwintering beetles is the humidity of the environment, which is significantly higher in heavy clay soils than in light ones sandy An additional negative factor that affects beetles in clay soil in combination with high humidity is its slightly reduced aeration.

Overwintering beetles are negatively affected by both very low and very high soil moisture. There is a direct relationship between the depth of beetles and soil moisture. Overwintering in dry soil goes relatively well, but in the spring, in soil with low humidity, restoring the water balance to the species norm in the body of beetles is difficult, and their reactivation is very slow. The beetles linger in the soil until rainfall and partially die. In the absence of rain, even at optimal temperatures, the emergence of beetles from the soil may be delayed for a long time (until September-October) and their death in such cases from drying out can be very high.

In very arid areas (Arizona in the USA, some areas of the steppe zone of Ukraine, etc.), heavier, moist soils are more favorable for wintering beetles than sandy ones, since they retain moisture longer and protect the beetles from drying out. According to Breitenbecher, in such areas, in moist soil, beetles are more easily reactivated and begin to reproduce more quickly than beetles emerging from dry soil.

Numerous observations in nature and experiments convincingly indicate the negative effect of high soil moisture on wintering beetles. Its influence is already felt during the period when the beetles leave the soil in the fall, when the beetles, due to high humidity, linger in the upper soil horizons and freeze out in severe winters. The mortality rate of beetles in moist soil is twice that of beetles in soil with low humidity. In the Kaliningrad region of the RSFSR, up to 75% of wintering beetles die annually in loamy, moisture-intensive soils. In Transcarpathia, the number of dead beetles in wetter clay soil is 3-7 times higher than in sandy soil. The negative effect of excessively high humidity is especially strong in the fall, during the rainy season, and in the spring, during snowmelt, when beetles are subject to periodic flooding. According to Scharfenberg, in soil flooded with water, beetles completely die on the 8th day. At positive temperatures, high humidity affects beetles both directly and indirectly, promoting the development of fungal, bacterial and viral diseases.

The death of beetles during wintering occurs unevenly. Vengorek established two periods of increased beetle mortality: autumn, when the beetles' diapause ends and metabolism increases, increasing the body's sensitivity to unfavorable environmental factors, and spring. During the winter months, beetle mortality is negligible. Particularly high mortality is observed in spring in clay soil, before the beetles emerge to the surface. According to Minder and Kozarzewska, the number of beetles that died in clay soil in March exceeded the number of individuals that died in the autumn months by almost ten times. In sandy soil, the difference in mortality rates in autumn and spring is smaller. These differences are due to the fact that beetles overwintering in sand have a significantly lower metabolic rate throughout winter dormancy than beetles overwintering in clay soil.

The transition from the active state to diapause is accompanied by significant dehydration of the body, accumulation of fat reserves in the fat body, a reduction in respiratory metabolism and changes in the activity of a number of tissue metabolic enzymes. In particular, the activity of tissue catalase increases significantly, which, as a rule, is proportional to the depth of physiological rest of insects. These changes provide hibernating beetles with increased resistance to adverse conditions during wintering.

During wintering, changes occur in the body of beetles, the size and activity of which largely depend on the wintering conditions. Analysis of the physiological state of beetles overwintering in different soils, carried out at different stages of wintering, showed that beetles overwintering in sandy soil are constantly in a state of deeper rest and maintain it longer than beetles overwintering in clayey soil. By the beginning of diapause, the amount of fat reserves in the body of beetles reaches 38-40% of dry weight. In winter, the dynamics of fat consumption in beetles overwintering in different soils is not the same: in clay soil fat is consumed more intensively than in sandy soil. High fat consumption occurs in the spring during the recovery period. Fat loss in beetles overwintering in sandy soil varied depending on generation from 17.1 to 29.0% in females and from 14.3 to 21.2% in males, while in beetles overwintering in clay soil , they fluctuated respectively within the range of 27.5-43.8 and 19.1-28.6%.

The water balance in the body of beetles during wintering also does not remain constant and correlates with environmental conditions. Beetles overwintering in clay have a higher water content in their bodies throughout the entire winter than in sand. In beetles overwintering in clay soil, the amount of water increases sharply in the fall and in the coldest winter months, the water content in their body almost reaches the level characteristic of active beetles, which entails an increase in the overall level of metabolism, which is correlatively accompanied by a decrease in the resistance of such beetles to the action of unfavorable environmental factors. In beetles overwintering in sandy soil, the increase in the amount of water in the body from autumn to spring occurs very gradually. Complete restoration of the water balance in these beetles is observed only before their spring awakening or even after their emergence to the soil surface.

Some other physiological indicators, for example, an increased intensity of gas exchange, also indicate an earlier reactivation of beetles overwintering in clay soil. In sandy soil, oxygen consumption is kept at a relatively low level throughout the winter. Judging by the intensity of oxygen consumption, the most profound suppression of metabolic processes occurs in beetles of the first early generation, overwintering in sandy soil. The activity of tissue catalase in beetles overwintering in light sandy soils is higher throughout the winter than in beetles overwintering in heavy clay soils, which also indicates a deeper and more stable state of physiological dormancy in which beetles are in sandy soil. The deeper dormancy of beetles overwintering in sandy soil is also evidenced by smaller changes in body weight (wet and dry) than in beetles overwintering in clay soil, in which they occur more intensely.

A comparison of the physiological state of beetles of the first early and late generations and beetles of the second generation during wintering shows that beetles of the first early generation, which have not started reproducing, are better prepared for wintering than beetles of the first late and second generations. The most profound suppression of metabolism observed in beetles of the first early generation during wintering in sandy soil provides them with the greatest stability during wintering.

The conditions created in the horizons of mass occurrence of wintering populations of beetles, in light sandy soils, promoting the preservation of long and deep dormancy, determine the formation of a protracted diapause in some individuals of the first early generation. In the spring, with the awakening of the beetles, their emergence to the soil surface and the beginning of feeding, the differences in the physiological state of the beetles associated with different wintering conditions are gradually smoothed out. However, beetles of the first early generation, which did not reproduce in the year of their hatching, awaken physiologically stronger in the spring.

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter.